Precedents

I. Institutional Rental Housing

Some state governments have, in the past, introduced policies that encourage rental housing through ‘rent-to-own’ schemes. Many such schemes, however, have been unsuccessful and therefore not replicable or scalable, with meagre rents proving to be insufficient to cover maintenance and management costs. A key learning has been that maintenance initiatives and costs have to be factored into the planning of such schemes and residents need to be sensitised on the importance of the upkeep of such properties. Additionally, the location and liveability of such units need to be prioritised to ensure success.

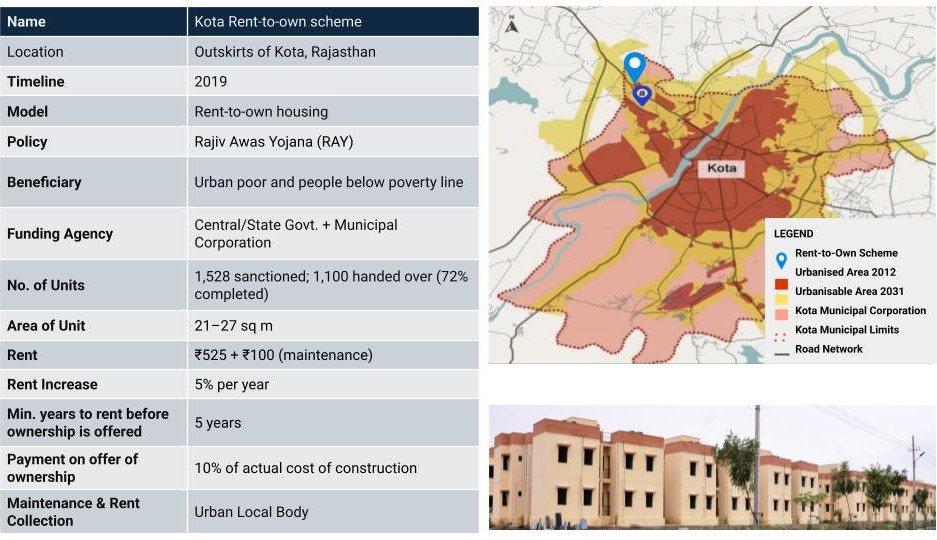

The Kota Rent-to-own Scheme requires tenants to pay a monthly maintenance charge to the Kota Urban Improvement Trust (UIT) to ensure adequate upkeep. However, as tenants increasingly transition to ownership, given the short renting period required, solutions to ensure long-term maintenance, like the formation of Residents’ Welfare Associations are being explored.

In the Chandigarh Small Flats Scheme, management of the properties, especially timely rent collection was a key issue. The project was also located in the outskirts of the city, making it difficult for inhabitants to access livelihood opportunities and thus earning sufficient income to pay rent. The additional costs to be paid to access basic services like electricity and water placed more strain on the finances of the residents. This inability to pay rent in turn placed additional stresses on the finances of the state government. The longer rental tenure before ownership was possible also made residents more likely to not be invested in the scheme.

In the case of the West Bengal Public Rental Housing Estates (PRHE), the annual maintenance costs were said to have been around ₹4 Crores while the rent collected only amounted to ₹30 Lakhs. Further, only 10–15% of the housing units built were sold, thus ensuring that the maintenance costs continued to drain state finances.

Rental housing has also been developed by the state or through Public-Private Partnerships (PPP). Similar rental management issues have been encountered in such projects.

Though the Mumbai Rental Housing Scheme was successful in drumming up interest from the private sector and was implemented across the MMR through multiple projects, management of the properties by the MMRDA was found to be financially unviable. Thus, the scheme was soon replaced by the Affordable Housing Scheme.

Affordable Rental Housing in the Indian Context

Kota Rent-to-own Scheme

Chandigarh Small Flats Scheme

West Bengal Public Rental Housing Estates (PRHEs)

Mumbai Rental Housing Scheme

II. Hostels

Housing for India’s working population is a necessity especially in metropolitan cities that experience a huge influx of professionals every year. There is a huge demand for rental housing at subsidised rates around major employment zones. However, the housing condition for migrant workers mostly remains bleak. To address this issue, the budget for 2024–25 emphasised the importance of rental housing with dormitory-type accommodation for industrial workers in a PPP model. Examples of this type of housing include the Vallam Vadagal Industrial Housing Project by FOXCONN in Tamil Nadu and the Sakhi Niwas Working Women’s Hostel in Mumbai by the BMC in partnership with an NGO. Additionally, some local government bodies have also introduced hostels for their working populations. Tamil Nadu has introduced several Thozhi Working Women’s Hostels across major cities in the state while Kerala has introduced the ‘Apna Ghar’ project that provides hostel facilities to migrant labourers. Similar need-based housing targeting different user groups is the need of the hour.

Vallam Vadagal Industrial Housing Project, Sriperumbudur

Sakhi Niwas Working Women’s Hostel, Mumbai

Thozhi Working Women’s Hostel at Guduvanchery, Chennai

Kerala ‘Apna Ghar’ Rental Housing for Labourers

III. Co-LIVING

In the private housing domain, co-living models are emerging as a solution for students and migrant professionals who can afford to rent in the formal market. Startups like Nestaway, Aarusha homes, Hive Hostels etc. offer a new form of paying-guest accommodation that ensures a hassle-free living experience where the maintenance, utilities, cleanliness of the property is managed by the company and the end-user simply has to move in with their belongings. This process skips the struggle of finding apartments through brokers, paying hefty amounts and physically searching for accommodation.

Aarusha Homes

Nestaway

Global Perspectives

In this section, we present the studies we have carried out on precedents from around the world to acknowledge and understand global perspectives on the importance of and approach to rental housing. The cities studied include New York City, Berlin, Singapore and Vienna.

I. New York City

Rental housing accounts for more than two-thirds of all housing in New York City (NYC). As of 2023, 68.1% of households rented their homes. However, it is notable that 52.1% of renter households were rent-burdened. 34% of rent-burdened tenants spent more than of their pre-tax income on housing in 2021; nearly 30% of low-income renters were severely rent-burdened.

In the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, the majority of rental units were either covered by some type of rent regulation — predominantly through the NYC rent stabilisation system, rent control, Mitchell-Lama, and other financial assistance programmes (CityFHEPS, Pathway Home, Rent Freeze, Housing Voucher) — or are part of subsidised or public housing developments.

II. BERLIN

1.66 million apartments rented out of a total of 2 million apartments in 2022 (as per Census). Only 15% of people in Berlin live in apartments they own while 82% live in rental housing. The remaining apartments either remain vacant or are used as leisure apartments.

The rental market primarily consists of two categories: long-term and short-term rentals. The stakeholders shaping the rental market include property management companies, real estate agents, individual landlords and property owners, and govt agencies. The majority of Berlin’s rented accommodation belongs to private landlords — these may be large property companies or private individuals. Six municipal housing companies — degewo, GESOBAU, Gewobag, HOWOGE, STADT UND LAND and WBM — manage 381,074 state-owned rental apartments. Over 80 housing cooperatives own and manage 205,020 rented apartments.

In 2019, social rental housing stock included around 95,000 apartments, with the majority being social rental apartments that were first subsidised until 1997 (around 93,000 apartments). However, this stock is expected to fall to around 59,000 apartments without new funding. This decline can be attributed to the expiry of commitments made during the strong funding years of the 1960s and 1970s as well as promotional loans that have been redeemed early due to historically low interest rates on the general capital market, thus shortening commitments to 10–12 years after early redemption.

Forms of rent regulation include rent freezes, rent caps, and restrictions on rental increases. Rent subsidies are also available to tenants living in social housing who pay rent that exceeds 30% of the household income (which cannot exceed income limits of Berlin by over 55%).

III. SINGAPORE

The major emphasis of Singapore housing policy has been on ensuring home ownership for its citizens. HDB (Housing Development Board) flats can only be sold to Singapore citizens and a fixed percentage from monthly salaries goes towards the ‘Central Provident Fund’ (CPF) which becomes a down payment towards buying housing. Home loan interest rates are on the lower side being 2–4% which enables home ownership even among young adults.

HDB developments are mostly 99-year leases, with land perpetually owned by the government. HDB flats need to be held for a minimum of five years before re-sale.

Renting is uncommon in Singapore and rental housing stock is created for low-income households. By design, most of the rental flats are studios and one-bedrooms, whereas ownership units are primarily two- to four-bedrooms.

IV. Vienna

Vienna’s social housing model was implemented in response to the upheavals of World War I. For a long time, Vienna’s social housing model also benefited from population decline in the city and access to cheap land as a result of taxing luxurious activities (such as horse-riding). 76% of Vienna’s population resides in rental apartments managed by Wiener Wohnen, a municipal management agency that takes care of repairs, structural retrofits and other maintenance requirements.

The great number of subsidised dwellings exerts a price-dampening effect on the entire housing market of the Austrian capital. Tenancy can be passed down to offspring or even siblings and the rents only increase with overall inflation — hence, rent expenditure does not occupy a greater percentage of one's salary. To avoid the creation of ghettos and the costly social conflicts that come with them, the city actively strives to ensure a mix of people from different backgrounds and on different incomes within the same estates.